The Metaphysics of the Sanskrit Alphabet

(The Metaphysics of the Sanskrit Alphabet)

by Ravi Khanna

gee_kay@vsnl.com

The Circle of Life

by M. C. Escher

Paper presented at the International Seminar on

SABDA: TEXT AND INTERPRETATION IN INDIAN THOUGHT

2-4 February 2004

Organized by Centre of Linguistics and English, Jawaharlal Nehru University

vaNa- iva&anaBaaYyaM

(The Metaphysics of the Sanskrit Alphabet)

I commence my talk with a quote from Dr. Kapil Kapoor’s paper – “Vivarta & Parināma – Bhartriharī`s Theory of Language” – 1996. He cites Rig Veda I.164.41 as follows …

gaurih mimāya salilāni takśati ekpadī dwipadī sā catuspadī

astāpadī navpadī babhūvusī sahasrāksarā parme vyöman

“ Gauri is the symbol of vāk or speech, according to the shrutīs …. the real significance is that the principle of vāk creates or fashions out the manifold forms out of the waters of the infinite ‘ocean of reality’ … the parme vyöman. You cannot cut forms or draw lines in water, you can do that only in space but ; but reality like water is continuous, indivisible…”

The word used here for ocean is salilâ which actually means the surging of waters, the expression here alludes to an agitated ocean, one in which the waves are being whipped up by the rage of the wind ; for salilâ also means a kind of wind . Thus speech is the giving of form to the upsurge in the consciousness – the innate desire for expression. And it is this desire that leads to the structuring of prānic energy into various meters and sounds.

At the very end of the Rig Veda – in the 10th mandala viz. X.190.1 to 3 the creation myth is given in its condensed form. Here the “ocean of energy” is called both the samudra and arnava. These various expressions explain the multiple states of the “ocean”…. samudra expresses the uniformity as viewed deep within the sea, while arnavah is the billowy-agitation on its surface. The word arnava is the group word for varna. What this means is that the external reality unfolds from arnava, the waves on the boundary of the vast “ocean of energy” and this reflects into our consciousness as so many varnas which are fashioned into manifold internal expressions to interpret this reality. As we will see ………..

Linear vs. Non-linear

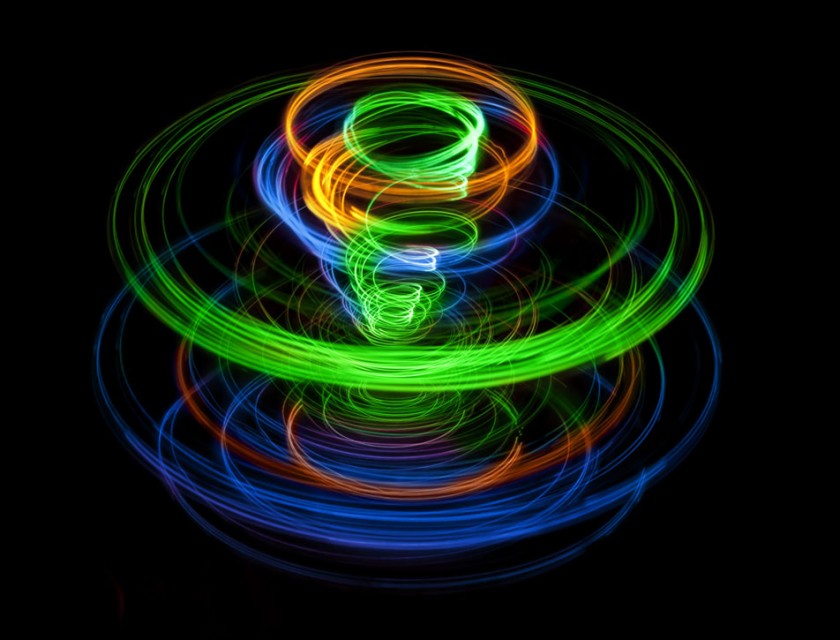

◊ It is this universe that we sense around ourselves that the Vedas refer to as the vast “ocean of energy”. On the western side we now understand that it is non-linear. There are symmetries within symmetries within symmetries – endlessly so, ranging from the very large to the extremely small (See Fig 1).  The Sanskrit alphabet reflects these macro and microcosmic symmetries in an elegant arrangement of varnas that can give rise to virtually any colloquial sound.

The Sanskrit alphabet reflects these macro and microcosmic symmetries in an elegant arrangement of varnas that can give rise to virtually any colloquial sound.

In a linear, idealistic world energy lends itself to simple cause and effect solutions – I push this object and it moves forward – in a ‘Non-linear’ equation this is not so. A push here may not result in an immediate effect there, the effects may collect over ‘space and time’ zones to precipitate entelechies, (insert definition) sudden occurrences or epiphanies which seem totally disconnected. Or small effects can cause huge changes. The advent of super-computers in the 1980s actually brought about the detailed study of these ‘Non-linear’ equations. Till then the large number of calculations required could not be done manually and since most technological applications were mechanical (or one can say ‘ordered’) nobody bothered about non-linearity or chaos. The Global weather problem was the first non-linear equation to be widely studied and Edward Lorenz showed in 1963 [1], how very small changes in weather patterns could precipitate huge changes thousands of miles away. He coined the phrase ‘the butterfly effect’ whereby he meant that a small butterfly flapping its wings in Peking could change the weather in New York. And this was prophetic indeed because the ‘El-Nino factor’ is now legendary. A small current in the Pacific has been empirically found to effect world weather.

In the early 1980s non-linearity gave birth to the fields of ‘Chaos and Order’ [2] and ‘Fractals’ [3]. The western scientists and mathematicians saw that in real-world problems there was no absolute size. As you scaled the solutions, that is looked at bigger or smaller sizes the same forms and designs kept repeating themselves endlessly. Chaos Theory and Fractals are today being applied to just about every subject ranging from economics, share prices to study of heart beats. The list is endless.

◊ In this paper we further show how the Sanskrit alphabet creates an isomorphism from external reality to discursive (unclear meaning) language. The non-linear arnava is harnessed in a collection of symmetrical varnas that act as a bridge between aham, the I-consciousness, and the creation that this consciousness looks back upon – to imbibe, to understand and to philosophize.

The meaning of ‘varna’

◊ Commonly, the units of vāk or speech, are referred to as the varnas . This means that they are the basic sounds, the phonemes. However, to my reading there is much more…..

The word varna comes from the dhātū , the root verb √vr which means ‘to cover’. See “ Nirukta “ [4] for the English version and “ inaÉ>ma ” [5] for the Hindi version. The passage describing varna includes the description of kalyān – varna – rūp threesome. Here kalyān is referred to the brilliance of shining-gold, varna – that which covers and rūp as beauty and its form. A later and more detailed explanation comes from “Amarakösa” [6] :-

varno dvijādau śuklādau stutau varnamtu va akśare.

aruno bhaskare api syāt+varna+bhede+api ca trsu .

varnah has two lineages viz. white etc. colours and stuti meaning eulogy, singing praise, panegyric. Thus it means both delineation of colours as well as delineation of sounds or varnam the letters, phonemes.

arunah is the name for the sun, for its red hue as it rises ; perhaps as a third meaning varna is the separation of the suns energies or rays.

Thus varna is expressed in the modern dhātukösh [7], dictionary of root verbs, as both varne and āvarne. The former means to choose, to limit ; while the latter means to cover, to hide.

As the mind selects little parcels of energy from the vast “ocean of energy”, that we have talked about earlier, it qualifies them as shape, sound, colour and so on. All this is varna, for varna is the intermediary between the Universal, the Unknown sea of moving energy (the jagatyāmjagat of Isāvāsyam Upanishad) [8] and our senses. For that which covers also exposes itself; reveals itself to the rest of us. This a very important concept : varnas are therefore units of ākritī, shape/form ; units of colour and they are the units of sound that appear as akśar, letters/phonemes, to our ears or śröt. If we were to take a small piece of clear glass and turn it towards the rising sun – it would partially cover the sun’s rays ; at the same time revealing a red hue and its own outline. This is how the varnas assist our minds in nomenclating and talking about the entire range of māyā.

◊ In a similar vein Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), an English poet puts it so succinctly : excerpted from an elegy – Adonais (passage # LII) :-

The One remains, the many change and pass ;

Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly ;

Life, like a dome of many-colored glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.– Die,

If thou wouldst be with that which thou dost seek !

Follow where all is fled ! – Rome’s azure sky,

Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words, are weak

The glory they transfuse with fitting truth to speak.

It is the varnas which bring about “Life, like a dome of many-colored glass” into our senses by giving us the instance to talk about and identify the “Flowers, ruins, statues, music, words…”.

◊ Another beautiful metaphor for varnas comes from the writings[9] of Shri Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888 – 1975), former President of India and a Vedic scholar of immense international repute says,

Māyā evolves a variety of names and forms, which in their totality is the jagat or the Universe. It conceals the eternal Brahman under this aggregate of names and forms. Māyā has two functions of concealment of the real and the projection of the unreal. The world of variety screens us from the real.

Some think Creation’s meant to show him forth,

I say it’s meant to hide him all it can.

Browning, “Bishop Blougram’s Apology”

“In Hindu thought, māyā is not so much a veil as the dress of God.” A dress serves two purposes – it hides and it displays. Likewise māyā can be likened to a scrim. A scrim is a thin canvas used in theater and opera in order both to show the audience shapes and colors and to hide what is going on backstage…..

The scrim therefore is like varnas , you illumine it from the rear and you can imbibe what is at the back ; you light it from the front and you can project on it like a cinema screen – the same varnas are used to utter the projected, spoken words.

◊ Graduating to vāk or speech from the level of akśhar or letters the Vedas say in Brihadāraṇyaka Upanishad I.6.1 :-

trayam vā idam nāma rūpam karma tesām nāmnām

vāg+iti+etat+esām + uktham +atah+hi sarvāni

nāmāni+uttisthanti . etad esām sāma+etat+hi

sarvaih+nāmabhih samam +etad+esām

brahma+etad+hi sarvānI nāmāni bibharti.

Coupled with Br. I.4.7 on Pg. 691 of the above reference this shlöka says :

All that is manifest in the visible universe is covered by the triad viz. nāma – rūpa – karma i.e. name/number, shape/form and action/work. Of these as regards names, speech is the source, for from it all names arise. It is their common feature ; for vāni or the spoken word is the foundation of all names. This speech can be likened to the Brahman, the Unknown, for from our memory of learnt speech the known names filter into our consciousness, ultimately they are nurtured back into the realm of vāni or speech as we speak about things.

Now let us go to the alphabet itself…

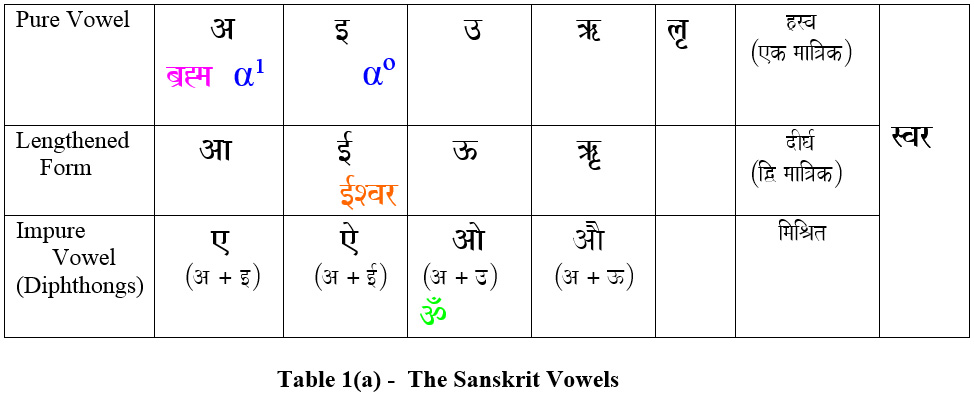

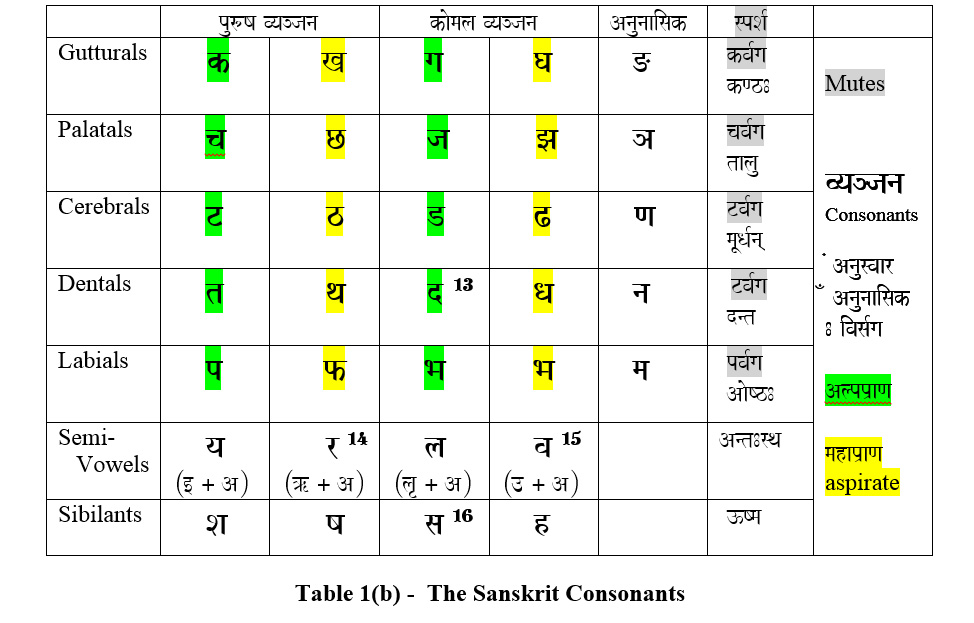

The Sanskrit Alphabet

Table 1. gives the complete alphabet. It is based on the Paniniya 14 Māheshwar sūtras. A detailed study has been given by Dr. Vidhātā Mishrā [10] in a critique based on the Śikśā and Prātiśākhya of the four Vedas. These ancillary texts were taught to the ancient śisya or students as prerequisite to the chanting of the Vedas.

◊ Yāska says in the Nirukta 2.14[11] & nirukttam[12] II.4:-

svah+ādityah bhavati – su aranah , su iranah , svrtah rasān,

svrtah bhasam jyotisam, svrtah bhāsā+ity vā. etain dhyauh+vyākhyātā.

svar is the name of the sun – it stands alone, dispersing darkness, it is the heavenly resonance, it lights up the luminaries or the other planetary bodies. svar is the shining light. This explains dhyauh – the celestial region, and its origin from the root word div, which means to be bright from within.

- The svar are the vowels. They are the shining sounds.

- The sparśa or the mute consonants are the reflected sounds.

Table 1. The Sanskrit Alphabet

Now, there are two types of bodies in the Universe viz. (a) those that shine and emanate energy themselves and (b) those that reflect light that comes from others – they are themselves ‘dark matter’. In fact the scientists are estimating the ‘dark matter’, which also includes the ‘black-holes’, as far more than the visible matter.

Now, there are two types of bodies in the Universe viz. (a) those that shine and emanate energy themselves and (b) those that reflect light that comes from others – they are themselves ‘dark matter’. In fact the scientists are estimating the ‘dark matter’, which also includes the ‘black-holes’, as far more than the visible matter.

◊ That the svars are the shining, pure phonemes is further confirmed by Brihadāranyaka Upanishad I.3.26 :-

tasya ha+etasya sāmnah suvarnam veda bhavati

ha+asya suvarnam tasya vai svar eva suvarnam

bhavati ha+asya suvarnam ya evam+etat+sāmnah

suvarnam veda .

He who knows that this Sāman, lyrical speech, is like gold obtains gold. For, indeed those svars, vowels or pure sounds are su + varna, also the word for gold. This is the Veda, or knowledge of the gold-nature of the Sāman.

Thus here the shruti equates svar, vowels or musical tones to su + varna, pure sound and hence derives suvarna, the word for ‘shining gold’ !

â, î, û (A¸ [ ¸ ]) – the pure vowels

◊ Now, â, î, û (A¸ [ ¸ ]) are the pure vowels. They are pronounced as follows :-

- â ( A ) is uttered from the expanded throat using samvrt prayatna or a contracted effort.[17]

- î ( [ ) is uttered from tālau jihvāmadhaym ivarne [18] or ‘the roof of the mouth above the tongue-middle’. It is palatal.

- û ( ] ) is uttered ‘by narrowing and rounding of the lips’.[19]

These three are spoken by just pushing the prāna or life-breath and the tongue is not moved but only positioned. The moment the tongue moves, as in speaking most of the other letters, the breath is reflected by it.

The importance of â, î, û (A¸ [ ¸ ]) can be understood from the shlöka :-

aum pūrnamadah, pūrnamidam, pūrnāt pūrnamudacyate

pūrnasya pūrnamādāya pūrnamevāvaśisyate. (Īś.Up.-1) & (Br.Up.- V.1.1)

This is the Shānti pāth at the beginning of Īśāvāsyam Upaniśad and it is also the first shlöka of the fifth adhyāy of the Brihadārānyaka Upaniśad. (This fifth chapter is the beginning of the third kānd or section, and is named khilakānd , the addendum). In both the Upaniśads this shlöka is importantly positioned. It means :-

Om That (Brahman) is Infinite, this (universe) too is infinite. The infinite (universe) emanates, originates from the Infinite (Brahman).

Assimilating the infinitude of the infinite (universe), the Infinite (Brahman) alone is left.

What is pūrna ? It is the root pūr, meaning full or complete and the suffix kta further stresses this meaning, making it more vehement or ‘that which is more than full’ i.e. Infinite. adah ( Ad: ) is ‘that’, a pronoun referring to something that is prökśa or ‘not known to the senses’. idam ( [dma\ ) is ‘this’, a pronoun referring to something that is pratyakśa or here and now. udañch ( ]dHca\ ) [20] is to arise from, to emanate. There are three layers of meaning here as follows :-

adah ( Ad: ) ; idam( [dma\ ) ; udañch ( ]dHca\ )

The syllables are two, three and four ; the â, î, û (A¸ [ ¸ ]) are each combining with the syllable d ( d ) to structure these layers and this is further explained in the next section comprising of three shlökas viz. Br.Up. – V.2.1 to 3. The latter explain the three d ( d ) as dam ( dma ), dān ( dana ), and dyā ( dyaa ) which are the qualities of the Gods, the Devas ; the people, manusya ; and the demons, the asuras respectively. This is asserted by the Goddess of speech, vāg devī as d – d – d (d – d – d ) the sound of the thunder in the clouds.

◊ â ( A ) therefore represents ‘that’ which is the Absolute infinity or Omega, Ω of Cantor’s theory of Infinities [21]. It is Brahman, the Unknown. It is the akśara ( Axar ), the indestructible or the â + swar ( A+svar ).

The following shlökas further underline the above assertions :-

Aitareya Ārāṇyaka II.3.6 [22]

….â+kāraḥ vai sarvā vāk+sa+eṣā sparśaḥ ūṣma abhivyaḥ+ajyamānā . bavhī nānā rūpā bhavati. tasyai yadupāṅśu sa prāṇo atha, yad ucchaiḥ tat śarīraṁ, tasmāt tat tir iva tir iva hai+śarīraṁ+śarīro hi prāṇo atha, yad uccaiḥ tat śarīraṁ, tasmāt tad āvira āvirhi śariraṁ.

……. ‘a’ is the whole of speech and being manifested through the mutes and the sibilants it becomes manifold and various. If uttered in a whisper it is this prāṇa, if forcefully, that body – śarīra. Therefore it is hidden, as hidden as the previous body encapsulated in this prāṇa . But spoken forcefully it is that body and visible, for body is visible.

‘a’ ( A ) is a suffix in every sparśa or ‘mute consonant’ – i.e from kâ ( k )[23] to mâ ( ma ) and in the sibilants śâ, sâ, sâ, hâ ( Sa¸ Ya¸ sa¸ h ). This is a very interesting structure in Sanskrit. Now not only ‘a’ ( A ) is a suffix in every consonant of the alphabet and from there it pervades into every spoken word or sentence, thus it is also the symbol for Brahman, the Unknown……and this is precisely what is restated by Lord Kriśna in Gītā 10.33…

akśarānām â+kārah asmi dwandwah sāmāsikasya ca. aham eva

akśayah kālah dhātā aham viśwatomukhah . 10.33

I am the letter ‘a’ among the vowels of the alphabet and the dwanda compound in relation to the words collectively. I am indestructible time. I am the Dispenser facing everywhere.[24]

Thus â ( A ) stands for Brahman, the Unknown…

◊ î ( [ ) is ‘this’ continuity at hand . It is the î+swar ( [|+svar ) or the īśwara, the God that is manifest and pratyakśa or lies within the realm of our senses. It is the Aleph 1, א1 – the continuous infinity of Cantor’s theory of Infinities[25]. It is uncountable, as rigorously proved in the reference, and from this emerges the countable infinity again and again without diminishing it.

idam( [dma\ ) is linked to Lord Indra , after whom our senses are named indriyān. (Indra appears in Rig Veda and is synonymous with the later concept of Īshwara , this is explained by S.Radhakrishnan[26] )…..

sa etameva purusambrahm tatmam+apaśyat. idamadarśam itīm.

tasmāt idamdro ha vai nām. tamidamindra santam+indra ityācakśate

prokśain . prokś+priyā iva hi devāh , prokś+priyā iva hi devāh .

Aitareya Ārānyaka II.4.3 & Aitareya Upaniśad I.3.14 [27]

He saw this purusa (the first born), as the constituent of the Brahman, over-spreading all. With wonder he said, idamadarśam – “Oh ! I have seen this.” Therefore He is called idamdra (idam+dra). Idamdram, verily is His name. Though He is indirectly called Indra. The Devas or Gods are fond of the cryptic ; the Gods are indeed fond of being called indirectly.

Thus î ( [ ) reflects “this” the tangible aspect of Brahman and it is synonymous with Īshwara or Īndra in various texts.

◊ û ( ] ) is the unfolding māyā, it is the measure of things as our consciousness moulds out forms in the formless ; it is Aleph – naught, א0 – the countable infinity of Cantor’s theory[28]. This next shlöka establishes how the udañch ( ]dHca\ ) can be understood as udgītah, the universal song of consciousness…..

esa u [29] vā udgīthah, prāno vā ut, prānena hīdam sarvam uttabdham,

vāg eva gīthā , ut ca gīthā ceti, sa udgīthah . Br. Up. I.3.23

And this û is udgītha, the universal song. The vital breath prāna is ut, for by vital breath is this whole creation upheld, supported. The universal song, verily, is speech. This is udgītha, for it is ut and gītha.

Thus û ( ] ) combines the life breath, prāna ; and speech, vāk together into our consciousness giving rise to this māyā or surrealism.

The number of ‘svars’.

◊ The number of svars, vowels according to the Paniniya Māhāsūtrās is 13. (See Table 1. above). Besides the three primary vowels discussed above there are two more r (pronounced ri) and l (pronounced Lri). These two are half-way between vowels and consonants since the tip of the tongue is used in pronouncing them.[30] In fact the Śiva Sūtras [31] term these two vowels as sandha or eunuchs. All these five vowels are of single sound i.e. of one mātrā.

The Atharvaveda and Rgveda Prātiśākhyas also give the number of svars as 13 ; those that commonly appear in the Vedic and the Purānic are included. This means that besides the above 5 there are lengthened forms of the first four only viz. ā, ī, ū, ŕ (Aa¸ [- ¸ } ¸ ?R ) and not that of l ( ; ). This brings the number to 9.

Now â combines with î to give ( A + [ ) as e ( e ) ; â combines with ī to give ( A + [- ) as ai ( eo ) ; â combines with û to give ( A + ] ) as ô ( Aao ) ; â combines with ū to give ( A + } ) as au ( AaO )– these vowels are called mixed or diphthongs, mishrit. Like the four lengthened forms these four diphthongs are also of double prosody, that is they have two mātrās.

The Solar system and the Sanskrit Alphabet

There is a shlöka in the Aitareya Ārānyaka II.2.4 which says [32] :-

vyañjanaih+eva rātri+ira+pruvanti svaraih+ahāni .

By the consonants the earth-nights are delineated. By the vowels the days.

The svars are the shining energies of the Sun. The consonants are the reflected energies of the moon. If â ( A ), as the symbolic Brahman, the Unknown, is suppressed among the 13 vowels then we are left with 12, the number of the Sun-signs.

The sidereal cycle of the Moon is 27.32 days and the synodic cycle, as viewed from Earth by us, is 29.53 days [33]. Now 365.25, the number of earth days in a year divided by 29.53 gives 12.37 and if we multiply this by two, to allow for the waxing and waning phases of the Moon, we get 24.74. This to the nearest whole number 25 is the number of sparśa or the mute consonants. (See Table 1).

For the sidereal cycle we get similarly 26.74 ; the number of lunar constellations in the Vedic system is 27 and is listed in the reference [34]. Each constellation marks thirteen degrees and twenty minutes of arc in the zodiac.

The Alphabet unfolds the sound energies or vāni as we view outwards from the Earth. This is called bhūgölik or earth-centric. If we view from the heavens downwards it is called khagölik – as seen from an external point of observation, and this gives rise to dhvani or music.

◊ The Taittirīya Upaniśad says right in the beginning (it is the 2nd shlöka of the Śīkśā Vallī, the first shlöka being the Śhānti pāth or the peace invocation of this particular Upaniśad) :-

aum śīksām vyākhyāsyāmah . varnah svarah . mātrā balam . sāma samtānah . ity + uktah śīksādhyāyah

This shlöka is more like a sūtra – a condensed form of a secret instruction :-

Prior to the study of the Vedas, the ancient student had to undergo the study of phonetics and pronunciation and this is being explained here as three phrases….

- varnah svarah – I have explained at length above that varnah relates to more than just sound – it refers also to units of classification and colour. However, this sūtra explains that it is restricting itself here to the purest of phonemes viz. the svars. The latter have been discussed above and we have shown them to be 13 at first count.

- mātrā balam – The first word mātrā literally means ‘meter’ or the measure of time taken in annunciating a letter. The accent or the stress is the balam which essentially gives strength to the chanting of the shlökas or mantrās . How does this come about ?

The vowels, svars alone carry the ‘meter’ and they are of three types – short vowels, hrasva ; long vowels, dīrgha and prolongated vowels, pluta. This creates an exhaustive list of 23 vowels as follows :-

â, î, û, r, l, e, ô (A¸ [ ¸ ] ¸ ? ¸ ; ¸ e ¸ Aao) are short.

ā, ī, ū, ŕ, ĺ , ai, au ( Aa ¸ [- ¸ } ¸ ?R ¸ ;R ¸ eo ¸ AaO ) are long.

â3, î3, û3, r3, l3, e3, ô3, ai3, au3 (Aa| ¸ [-| ¸ }| ¸ ?R| ¸ ;R| ¸ e| ¸ Aao| ¸ eo| ¸ AaO|) are protacted

The consonants combined with these metered vowels give a rhythmic, chanting pattern to the mantrās and these rhythms have seven basic structures called chhandâs . Now, interestingly the basic count for the number of syllables in these chhandâs varies from 24 to 48 increasing in steps of 4. These are gāyatrī (24), usnik (28), anustup (32), brhatī (36), pankti (40), tristup (44) and jagatī (48). Pt. Motilal Shastri (1908 – 1960), a vedic scholar of rare insight has written vigyānbhāsyam or scientific treatise on a number of Upaniśads and the Śatpath Brāhmana. He explains [35] that the Earth has a 24o ( 23.5o to be precise) tilt in its orbit, to us therefore the Sun appears to move from above the tropic of Capricorn to above the tropic of Cancer by an angle of 48o approx. in its annual swing. It is this degree of change that the Vedic chhandas reflect and this is further underlined by the fact that the middle chhanda is called brhatī (36), ‘the largest’ even though it is in the centre. This is because the Sun is the brightest at the Equator, in-between the two tropics.

Besides the meter the mantrās also have three accents associated with their annunciation [36]. When a syllable is stressed it is called udātta, literally meaning acute or high. Then there is anudātta, which is neither high nor low, it is grave or middle. The latter is indicated in old vedic texts by a line below the syllable. The last is svarita, which is low. This is marked by a vertical line over the syllable in ancient vedas and brahmanās. These accents lead us to the musical notes – quoting Pānini, the 5th century B.C. vedic scholar, S. Bandyopadhyaya says in his book “the Origin of Rāga” [37] that the rising note or sound is udātta ; anudātta is the accent coming down the scale following this rise and svarita is flat or the accent that is ‘not raised’.

This then leads us to the third part of the shlöka…

- sāma samtānah – sāma ( saama ) literally means ‘uniformity’. It is also the name of the third veda that is considered the origin of Indian music. sama ( sama ) is the prefix denoting ‘sameness’ as in the word samsāra , which denotes the uniformity of the world around us. As a word, sama stands for the beginning and the ending note of the musical scale – and they are both the same because the notes follow a cyclical pattern from one scale into the other. samtānah therefore means the uniform rhythms which give rise to this musical scale…

As we see from the heavens, we have a khagölik view of the Earth. The seven ‘lights’ in the sky are the Sun, Moon and the five planets visible to the naked eye. This symmetry is reflected into dhvani or music. The primary seven notes are sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni [38] which are also termed svars or the shining ones, just like the vowels of the Sanskrit language. If we take the first four we get the name sargama or what we now call the musical scale in the Indian classical system. These seven ‘lights’ are also the basis for the names of the days of the week [39]. These seven svars are also accented – ga and ni are udātta ; re and dha are anudātta and sa, ma, pa are svarita. Thus when the mantrās are chanted it is these notes which are followed. This then is where language and music meet to give us the essence of both the terrestrial and the heavenly sound energies.

Now, there are four semi tones or komal svars viz. for re , ga , dha and ni ; there is one acute tone or tīvra svar viz. for ma. Added to the pure seven notes the count now becomes 12 and this again reflects the symmetry of the sun-signs. All the present day rāgas are based on the selection of 7, 6 or 5 notes out of these 12. And in an Indian classical music composition you can go up the scale in one rāga and come down the scale in another. Here it is called the āröha and the avaröha.

The twelve svars outlined above are based on a finer scale of sounds called the shrutis literally translated as ‘inner sounds’. In the first shlöka of ‘Sangītratnākar’ [40], a 13th century exposition on music Śarangdeva says :-

brahmgranthi+jamaruta+anugatinā cittain hrtpañkaje

sūrīnām+anu+rañjakah shrutipadam yo ayam svayamrājate

The anāhat chakrā is located in the hrdaya, the heart. anāhat means that which is unbroken. This shlöka says that the ‘life-force’ or prāna – vāyu is like a small tight knot that arises from Brahman, the Unknown. This enters the human body through the nābhi or the navel and rises undifferentiated to the inner core of the heart, the citta. This is the pranava ( p`Nava ) [41] or the collection of shrutis. Interestingly, shruti has two meanings.

- i) In terms of music it means the smallest discernible interval of pure sound. They are 22 in number [42]. These shrutis can be played on the dhruva veenā, an instrument with 22 strings, but they are too many to sing through the kantah, the throat – also the place of the viśuddhi chakrā. The shlöka says that in the heart of adept musicians the shrutis blossom as the twelve-leafed lotus of svars or notes. These twelve notes shine through the vocal chords as thousands of rāgas, each having its own time of singing during the day or even seasons. These are based on a very elaborate system of grāms, mūrchannās that later gave birth to thāths.

- ii) In terms of speech, shruti means mantrās, inspired within the enlightened mind of the rishīs, the ancient wise men. These shrutīs descended as direct knowledge into their heightened senses as they meditated upon the mysteries of the Universe. This is the shrutipadam of the shlöka and it is how the Vedas originated. It is almost as if Brahman, the Unknown found a way, a window down through their sahasrāra or the crown chakra, into their mana ( mana ) or consciousnesses. From here the unbroken shruti finds voice via the vocal chords and the mouth cavity in the elaborate system of phonemes, letters, words etc.

Interestingly of the 22 shrutis in the Indian music system [43] only one name röhinī is common with the names of the lunar constellations [44]. This is in the division of the musical note dhaivat. The lunar constellation röhinī which is now in Taurus was the vernal or spring equinox in 3000 B.C. This shift is due to the precession of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun and this larger circle takes 25200 years to complete. Thus every 900 years approx. the zodiac shifts by one lunar-sign. It takes 2200 years approx. to shift by one Sun-sign. The fundamental note of the musical scale is at present in shadaj but it was not always so. In 3000 B.C. the fundamental note was six shrutis earlier in dhaivat. In fact the name shadaj itself means ‘born of the sixth’ [45]. Thus every 1000 years approx. the traditional vocal music gharānās or families are to correct the fundamental by one shruti to compensate for the precession of the Earth.

The Mute Consonants – sparśa

◊ The sparśa are 25 in numbers as shown above in Table 1. To create the isomorphism from external reality to discursive language as we speak, the first mute ‘k’ ( k ) to the last mute ‘m’ ( ma ) – the glottis to the labials are traced and the entire mouth is virtually ‘shaped’ in these varnas. They are divided into five classes of five each :-

kavarga ( kvaga- : k¸ K¸ ga¸ Ga¸ = ) these are kanthasth or guttural ;

cavarga ( cavaga- : ca¸ C¸ ja¸ Ja¸ Ha ) these are tālavya or palatal ;

tavarga ( Tvaga- : T¸ z¸ D¸ Z¸ Na ) these are mūrdhana or cerebral ;

tavarga ( tvaga- : t¸ qa¸ d¸ Qa¸ na ) these are dantasth or dental ;

pavarga ( pvaga- : p¸ f¸ ba¸ Ba¸ ma ) these are östh or labial ;

If we look at them column-wise then the last column of five are nasals or anunāsik. In each class the first two have a harsh tone and are considered purusa or male while the 3rd and the 4th are softer and hence called kömal. At the same time the 1st and 3rd use lesser breath therefore they are termed as alp-prāna while the 2nd and the 4th are aspirates, using more life-force and hence they are termed māhā-prāna.

In short we see that the sparśa, mute-consonants have symmetries that are related to manifestation of life and its substance.

Paninī has explained a system of pratyāhāra or abbreviation in which the first and the last letter actually include the entire list between them. Thus kam ( kma ) would stand for the entire list of mute consonants. Now we look at the Brihadāraṇyaka Upanishad I.2.1 which is the first shlöka of the ‘Hymn of Creation’ [46] as follows:-

naiveha kimcanāgra āsīt. mrtyunaivedam āvrtam āsīt, aśanāyayā, aśanāyā hi mrtyuh ; tan man’kuruta, ātmanvī syām iti. so’rcann acarat, tasyārcata. āpo’jāyanta arcate vai me kam abhūd iti ; tad evārkasya arkatvam ; kamha vā asmai bhavati, ya evam etad arkasya arkatvamveda.

….There was nothing whatsoever here in the beginning. It was the absence of time or mrtyuh, death that hid everything. For aśnāyā or that which has not emanated, in other words is unmanifested is death. This aśnāyā- mrtyuh or the Unnameable, Brahman had a first thought in His mind, ‘Let me be’. This generated the first movement of thought and from this worship āpo emanated.…..’Verily’, he thought, ‘since my first desire has given rise to kam (within me)’, therefore this is the essence of energy or arka of all creation – he who understands kam thus comprehends the meaning (and control) of arka.

Both āpo and kam are hurriedly translated as ‘water’ in English versions of this shlöka. They are actually both ‘first’ emanations. Due to the desire to be, the infinite One expresses duality, right here the bifurcation of the internal mind and the external manifestation happens. āpo thus is the outward pervading matter, the plasma that is synonymous with arka or the very essence of energy ; kam is the expansion of thought within, turning into the seeds of the language , like Bhartrhari’s sphöta. It germinates the links of words and sentences, helping to precipitate the very first desire into action.

◊ The very first sparśa ‘ka’ is the vedic aphorism for Prajāpati a reflection of Brahman. Śatpath Brāhmana simply asks – “Who is the Unknown ?” and since kah ( k: ) in Sanskrit means ‘who ?’ this then is the obvious ‘name’ for that which cannot be named.

Now Chāndogya Upaniśad IV.10.5 establishes the duality of Brahman, the Unknown’s desire to be by saying that…..kambrahma, khambrahma……te ha+ūcuh+yad+vāva kamtad+eva khamyad+eva kham tad+eva kamity…

Here Agnī Deva, the Lord of Energy is explaining the secret of Brahman manifesting as different forms of fire or energies in the Universe. He says just as kam is the Infinite so is kham.

As I have explained above that īśwara, is the manifest or pratyakśa form of the Unknown that lies within the realm of our senses. Synonymously kam too is like Aleph 1, א1 – the continuous infinity of Cantor’s theory of Infinities. It too is uncountable and from it can emerge another infinite number of roots, words, sentences and so on that can name every possible form of creation. Then in the manifest speech of the sparśa the kham is the reciprocal of the Aleph 1, א1 . This transformation gives the same diversity to kham as is available in kam. Mathematically speaking :-

( KM )kham = _____1______ = _1_ = ~ zero

kam א1 ….Fig. 1

This is confirmed by Brihadārānyaka Upaniśad V.1.1 which continues after aum pūrn amadah, pūrnamidam,………aum khambrahma……

and also by the fact that kham means zero, śūnya in all ancient mathematical references. This also leads us to the concept of vacuum or space meaning ākāśa.

The Alphabet & the seven Chakrās of the Śiva śutras.

◊ We are going to look at two sūtras of the Śiva sūtras from the Vimarśinī by Kśemrāja written in 10th century A.D. [47] :-

I.6 Sai>caËsaMQaanao ivaSvasaMhar ..6.. – śaktichakra samdhane viśvasamhāra

II.7 maatRkacaËsambaaoQa: ..7.. – mātrkā chakra sambodhah

If we look at the Earth as shown in Fig. 2 we realize the entire life is restricted to a thin crust of about 30 Km thick on the surface plus few kilometers up in the air. As we look at this we can feel its ‘Mother nature’ ; the Gaia Hypothesis of James Lovelock seems so true that this prithivi purush itself is alive ; not only that it supports other forms of life. The Nirukta [48] (2.8) first relates the root ( maa ) √ma to mātā which means “the atmosphere” encircling the earth. This also means the “mother’s womb” in it the ātmā : soul takes shape and form and is born in this world. Just like the womb encloses the child and protects it, similarly the

The Nirukta [48] (2.8) first relates the root ( maa ) √ma to mātā which means “the atmosphere” encircling the earth. This also means the “mother’s womb” in it the ātmā : soul takes shape and form and is born in this world. Just like the womb encloses the child and protects it, similarly the

atmosphere covers the earth. Note that māta – ātmā are conjugal words.

◊ Brihadāraṇyaka Upanishad I.2.2 the 2nd shlöka of theymn of Hymn of Creation ‘Hymn of Creation’ says :-

āpo va arka, tad yad apām śara āsīt; tat samhanyat, sā prithivī abhavat ; tasyām aśramyat ; tasya śrāntasya taptasya tejo’raso nirvartatah agnih.

In this shlöka the external is being developed : The first spread, āpo is that of arka [49]. This is translated as fire, lightening, the sun in short various forms of cosmic energies. This coagulates and a layer is formed on its surface – śara is the thin spread of hardened cream on the surface of a bowl of milk. This then is the ‘crust of life’ on prithivi, the round globe, the Earth.

This is the first level of sambodhah or understanding of the sūtra II.7 – mātrkā chakra sambodhah.

◊ The next shlöka I.2.3 says in the beginning : sa tredhātmānam vyakuruta, ādityam tritīyam, vayum tritīyam, sa esa prānah tredha vihitah….

Here the internal is being developed : the ātmā is now conceived and its prāna or life-breath has three constituents of the divine viz. agnī itself, that enters through the nābhi or the navel, the Manipur chakrā ; vāyu the air, that together with agnī is the prāna-vāyu that we have talked about earlier ; this enters through the throat or the viśuddhi chakrā ; thirdly the āditya or the shining divine light, in other words the seed of consciousness that enters the foetus through the crown or the sahasrāra chakrā.

This then is how the second ātmā , the individual self, aham that is other than the Creator forms in the womb, mātā and the next shlöka I.2.4 says in the beginning : sah akāmyat dvitīyo ma ātmā jāyeti, sa mansā vācam mithunam….

The mana or the mind reflects from the ādityam and the vāca arises from the prāna ( or agnī-vāyu combine) and the whole play of māyā commences….

This is how the shaktī chakrās of the sūtra I.7 start getting framed.

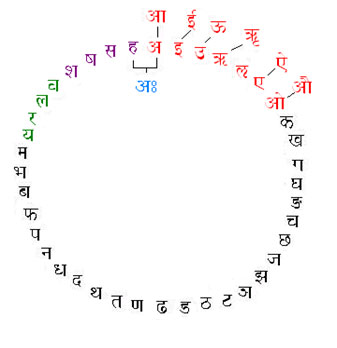

◊ In the Śiva sūtras matrkā also stands for the string of the alphabet. Now, I present these in the form of a chakrā as shown in Fig. 3. We look at Aitareya Ārānyaka II.3.6 again :

We look at Aitareya Ārānyaka II.3.6 again :

……. ‘a’ is the whole of speech and being manifested through the mutes and the sibilants it becomes manifold and various. If uttered in a whisper it is this prāna, if forcefully, that body – śarīra. Therefore it is hidden, as hidden as the previous body encapsulated in this prāna . But spoken forcefully it is that body and visible, for body is visible.

Now â ( A ) is the immutable, the symbolic Unknown – if this is the whisper, then as we force the breath just a little, what we get is its aspirate sound ah ( A: ) which is the visarga sound. Technically it is not included in the alphabet and is termed ayogavāh or ‘that which is not part of the harness’.

Thus we see another level of symmetry emerges – ah ( A: ) closes the circle pictorially – signifying the internal/external division as the ātmā shapes in the mātā. The ‘individual’ ego, ahamkāra ( AhMkar ) has thus taken form – there is an inside and there is an outside – with the language of consciousness as the dividing membrane !

◊ This is affirmed by a set of shlökas from Brihadāranyaka Upanishad – V.5.1 to 4 – the 1st shlöka says that at the beginning of this You-niverse there was just āpo and from this germinated satyam, the truth which is likened to the Brahman (this shlöka gives the three syllables of satyam as sa , ti , yam , the first and the last being real and the second unreal, madhyato anrtam – the fleeting is enclosed on both sides by an eternity which is real). The 2nd shlöka says – what is true is the yonder sun, ādityah. The purush (here the Universe is personified) who is there in the mandal and the purush (the individual observer) who is here in the right eye, these two rest in each other. The 3rd shlöka invokes the Gāyatrī mantrā equating the head, arms and the legs to bhū, bhuvah, svah and says that the name of the purush in the mandal is ‘ahh’ ( Ah: ). The 4th shlöka is identical to the previous except for the name of the purush in the right eye, it is aham (AhM ). Interestingly there is a fourth vyāhrti of the Gāyatrī mantrā that is beyond bhū, bhuvah, svah and it is mah ( mah: ) – the very opposite of aham (AhM ). These two are conjugate words.

ah ( A: ) is the bīja-mantrā for the crown or sahasrāra chakrā. This completes the explanation of – mātrkā chakra sambodhah. See Fig. 4 aham is to be understood as ah with the bindu on top as the anunāsik or the nāda bindu. This is also the bindu of aum ( ! ) which is the bija-mantrā for the ājna chakrā located in the centre of the forehead, exactly where the traditional tikā is to be placed in the Hindu religious practices. This is the point to which , during meditation, all the lower chakrā energies are to be collected for the final release of the ātman back into the Unknown. aum ( ! ) can also be understood as the pratyāhāra for all the vowel plus mute-consonant sounds and hence the complete definition of the vocal apparatus starting from the glottis to the lips. This completes the explanation of – śaktichakra samdhane viśvasamhāra.

aham is to be understood as ah with the bindu on top as the anunāsik or the nāda bindu. This is also the bindu of aum ( ! ) which is the bija-mantrā for the ājna chakrā located in the centre of the forehead, exactly where the traditional tikā is to be placed in the Hindu religious practices. This is the point to which , during meditation, all the lower chakrā energies are to be collected for the final release of the ātman back into the Unknown. aum ( ! ) can also be understood as the pratyāhāra for all the vowel plus mute-consonant sounds and hence the complete definition of the vocal apparatus starting from the glottis to the lips. This completes the explanation of – śaktichakra samdhane viśvasamhāra.

The Semi-vowels – the antahstha

These are four in number and are framed as follows :-

î combines with â to give ( [ + A) as ya ( ya )

r combines with â to give ( ? + A ) as ra ( r )

l combines with â to give ( ; + A ) as la ( la )

û combines with â to give ( ] + A ) as va ( va )

These antahstha are so called because they are in-between the vowels and the mute consonants. However, the prefix antar means both ‘intermediate’ as well as ‘internal’. Thus they reflect the inner energies of the body or śarira. They represent the bīja-mantrā of the lower four of the seven chakrās according to the Śiva sūtras.

These are as follows :-

( ya ) is for the 4th, the Heart or anāhat chakra

( r ) is for the 3rd , the Navel or manipūr chakra

( va ) is for the 2nd, the genitals or swādhisthān chakra

( la ) is for the 1st, the lower Pelvic or mūladhār chakra.

These are also called the yam ( yama\ ) symbols. And this is the name of Lord of Death in the Vedas thus signifying time-bound decaying of energies. Interestingly if we look at the Alphabet-ring in Fig. 3 ( ma ) and ( ya ) are contiguous. If we go clockwise yam ( yama\ ) could be the pratyāhāra for the entire alphabet signifying its closure or death. On the other hand if we go anti-clockwise from ( ma ) to ( ya ) and add an extra mātrā or meter to each syllable for extension in time – we get the unfolding of māyā !

The Shakti symbols – the ūsma

These are also called the Sibilants or Fricatives. The ūsma are śâ ( Sa ), sâ ( Ya ), sâ ( sa ) and hâ ( h ). The latter is the aspirate which we have covered earlier in the explanation for ah ( A: ). It is also the bīja-mantrā for the throat or viśuddhi chakrā.

The rest can be linked to the three Śaktīs viz. shri ( SaR – laxamaI ), usā ( ]Yaa ) & satī ( satI )…the energies of the manifest universe. Their consorts are Brahmā , Visnu and Śivā in various myths in the purānas or ancient legends. In the vedic sense energy is treated very differently from the western scientific method.

shri is the domain of counting. This belongs to Cantor’s, Aleph – naught, א0 – the countable infinity. Here the energy transactions are conserved. That is what diminishes from one place increases at the receiving end. This is the Goddess Lakśmī, of wealth. If I give you anything, say money, it reduces with me but adds to your account.

usā is that which keeps getting replenished from without. It is like Aleph 1, א1 – the continuous infinity of Cantor’s theory of Infinities ….the rays of the ādityah, the sun ; the flowing rivers are all examples of this form of śakti. I go to the river and fill a bucket of water, the flow of the water is not affected and I receive my nourish.

satī is the ‘energy that grows’ by giving. It is like the fruits of a tree that multiply or the dispersion of knowledge or like lighting many candles with one and so on. I give you a lesson – I do not lose it but you have gained. This increase is the brh and is the process of going back into the non-linearity.

There are many metaphors of these three Śaktīs in the scriptures.

Conclusion

We have seen that these varnas of the Sanskrit alphabet have a number of symmetries built into their structure. There is a clear metaphysical basis that needs far more analysis….its root forms, its meters and other structures give one the feeling of the unfolding of Dimensions. In fact it feels, looking at the – Fig.3 that a lot of knowledge is still to unfold and the resonances could lead to endless possibilities.

In conclusion Rabindranath Tagore’s lines from ‘The Gitanjali’ come to mind where he attempts a journey beyond words using the “heart’s – flute” as the mantric metaphor conjoining all life’s sounds into its mellifluous mould …

O silence him now, your poet

of words that race;

take his heart’s – flute, and play it

with deepest grace.

In the night’s depth let it sound

with a melody profound,

the flute – song with which you astound

the worlds of space.

Whatever in life and death is flung

about of me,

may this tune draw it to your feet

in harmony.

The clutter of words of day on day

in an eye – blink will float away,

and I shall hear the flute play, in

night’s endless place.