Gyān and Vigyān

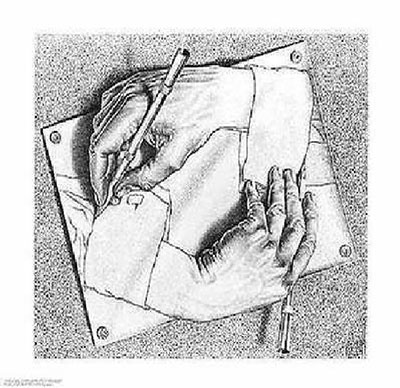

Figure – Figure , by Scott E. Kim (Sketch, 1975)

Figure – Figure , by Scott E. Kim (Sketch, 1975)

(Pg. 69 – “Gödel, Escher & Bach” by Douglas R. Hofstadter)

presented to Indian Insitute of Advanced Studies, Shimla

Seminar on INDIAN KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS

Gyān and Vigyān

I applaud the Indian Institute of Advanced Study at this initiative of chikitsa in our present day education systems. The timing is very correct since our dependence on the Western system that we inherited from the British has run its full course. This very West today is tiring with its technologies and fragmented areas of specializations, looking seriously towards the East for alternative, holistic systems of knowledge. This is best summarized in a recent Time magazine[1] special issue article “Your Mind Your Body” – I quote, –

‘If you close your eyes and think about it for a while, as philosophers have done for centuries, the world of the mind seems very different from the one inhabited by our bodies. The psychic space inside our heads is infinite and ethereal; it seems obvious that it must be made of different stuff than all the other organs. Cut into the body, and blood pours forth. But slice into the brain, and thoughts and emotions don’t spill out onto the operating table. Love and anger can’t be collected in a test tube to be weighed and measured.’

René Descartes, the great 17th century French mathematician and philosopher, enshrined this metaphysical divide in what came to be known in Western philosophy as mind-body dualism. Many Eastern mystical traditions, contemplating the same inner space, have come to the opposite conclusion. They teach that the mind and body belong to an indivisible continuum.

In the past, doctors and scientists have tended to dismiss that view as bunk, but the more they learn about the inner workings of the mind, the more they realize that in this regard at least, the mystics are right and Descartes was dead wrong.”

◊ But this is exactly what Lord Krishna explains to Arjun in Gita 7.2 [2] thousands of years ago……..that both the internal and the external domains of knowledge are important to reach Me the Ultimate reality…..

yaj&a%vaa naoh BaUyaao|nyaj&atvyamavaiSaYyato ..

jñānam te ‘ham savijñānam idam vaksyāmī aśestah |

yat jñātvā ne ‘ha bhūyo ‘nyat jñātavyam avaśisyte ||

I shall teach you in full this (self) realization combined with the (external) knowledge, which being known, nothing more here remains to be known.

Ramanuja interprets [3] this more closely and explains that – “jñāna is knowledge of (Me) the Universal Truth whereas vijñāna is the study of Myself in multitudinous distinctive forms that this Truth disperses into – both animate and inanimate”. In other words jñāna is meditative and draws towards the underlying Oneness of all things while, vijñāna is external – it measures, dissects, analyses. As the aspirant or sādhak painstakingly collects the knowledge of smaller truths step by step, he reverses this dispersal in his own consciousness, tending towards pragyānam Brahman [4] or the Ultimate Truth paradoxically the Unknown.

The Sanskrit word for truth is satyam which S. Radhakrishnan [5] explains as follows ….

The Brhad-āranyaka Upanishad (V.5.1) argues that satyam consists of three syllables, sa , ti , yam , the first and the last being real and the second unreal, madhyato anrtam. The fleeting is enclosed on both sides by an eternity which is real….

So the entire educational process should chip away at this ephemeral ti and lead the student to samyam ( saMyama ) or equipoise.[6]

◊ This synthesis of “Gyān-Vigyān” started in the West with the need to modify Classical Mechanics in the 1920’s …The scientific dilemma of this time has been[7] precisely outlined by P.A.M. Dirac in the introduction of his text book on Quantum Mechanics….

“The necessity to depart from classical ideas when one wishes to account for the ultimate structure of matter may be seen, not only from experimentally established facts, but also from general philosophical grounds. In a classical explanation of the constitution of matter, one would assume it to be made up of a large number of small parts and one would postulate laws for the behavior of these parts, from which the laws of matter in bulk could be deduced. This would not complete the explanation, however, since the question of the structure and stability of the smaller parts is left untouched. To go into this question, it becomes necessary to postulate that each constituent part is itself made up of smaller parts, in terms of which its behavior is to be explained. There is clearly no end to this procedure, so that one can never arrive at the ultimate structure of matter on these lines. So long as big and small are merely relative concepts, it is no help to explain the big in terms of the small.

At this stage it becomes important to remember that science is concerned only with observable things and that we can observe an object only by letting it interact with some outside influence……..The concepts of big and small are then purely relative and refer to the gentleness of our means of observation as well as to the object being described. In order to give an absolute meaning to size, such as is required for any theory of the ultimate structure of matter, we have to assume that there is a limit to the fineness of our powers of observation – a limit which is inherent in the nature of things and can never be surpassed by improved technique or increased skill on the part of the scientist…”

But the Gyān of the Upanishads starts at this point and Brihad-āranyaka Up. III.8.8 says of Brahman , the Ultimate that cannot be known…

He said; ‘That, O Gārgi, the knowers of Brahman, call it the Imperishable. It is neither gross nor fine, neither short nor long, neither glowing red (like fire) nor adhesive (like water), (It is) neither shadow nor darkness, neither air nor space, unattached, without taste, without smell, without eyes, without ears, without voice, without mind, without measure, having no within and no without. It eats nothing and no one eats it. [8]

So this, the Brahman, is the very fabric of reality….and yet not reachable and at another place in the same Upanisad [9] the famous neti neti (not this not this) argument sums this up – ‘ Now therefore there is the teaching, not this not this for there is nothing higher than this, that He is not this. Now the designation for him is the truth of truth. Verily, the vital breath is truth, and He is the truth of that. ◊ This limit which is inherent in the nature of things was tackled by the minds of a whole bunch of scientists like Bohr, Pauli, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Dirac, De-Broglie which led to the development of Quantum Mechanics – this is best excerpted in the words[10] of John Wheeler (1911 – present), (a physicist, who worked with Niels Bohr the main force behind of QM) writes….

◊ This limit which is inherent in the nature of things was tackled by the minds of a whole bunch of scientists like Bohr, Pauli, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Dirac, De-Broglie which led to the development of Quantum Mechanics – this is best excerpted in the words[10] of John Wheeler (1911 – present), (a physicist, who worked with Niels Bohr the main force behind of QM) writes….

(See Appendix – ‘Poetry’ – ‘Brahma’ by Ralph W. Emerson)

“Nothing is more important about the quantum principle than this, that it destroys the concept of the world as ‘sitting out there’, with the observer safely separated from it by a 20 centimeter slab of plate glass. Even to observe so minuscule an object as an electron, he must shatter the glass. He must reach in. He must install his chosen measuring equipment. It is up to him whether he shall measure position or momentum.[11] To install the equipment to measure the one prevents and excludes his installing the equipment to measure the other. Moreover, the measurement changes the state of the electron. The universe will never afterwards be the same. To describe what has happened, one has to cross the old word ‘observer’ and put in its place the new word ‘participator’. In some strange sense the universe is a participatory universe.”

Fritjof Capra[12] writes in The Web of Life……… …..

“This is how quantum physics shows that we cannot decompose the world into independently existing elementary units. As we shift our attention from macroscopic objects to atoms and subatomic particles, nature does not show us any isolated building-blocks, but rather appears as a complex web of relationships between the various parts of a unified whole.”

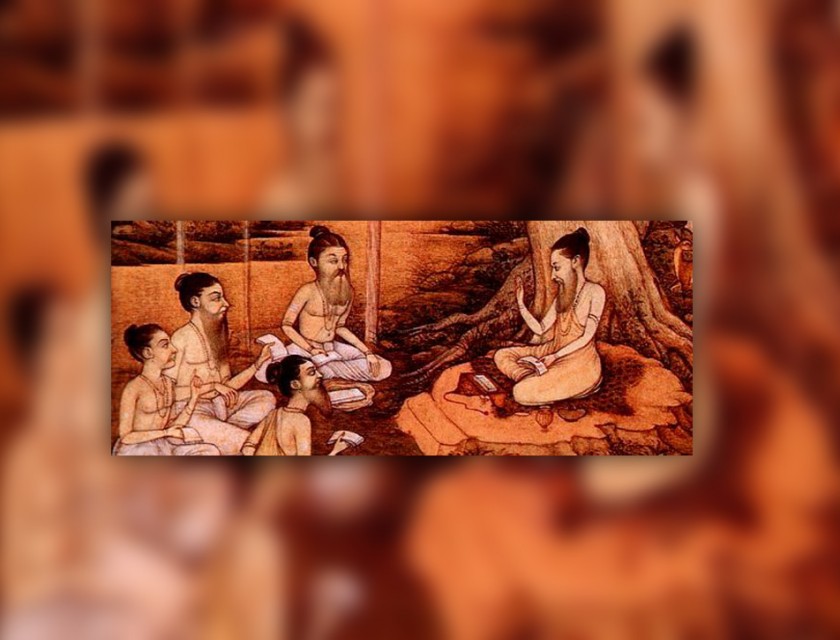

◊ The Upanisadic concept of Ātman was now touched upon by the West. To truly understand this let us start with the words of S. Radhakrishnan[13]… “as Brahman is the eternal quiet underneath the drive and activity of the Universe, so Ātman is the foundational reality underlying the conscious powers of the individual”… The various Hymns of Creation in vedic writings dwell on this Brahman – Ātman dichotomy in a variety of ways – it is like a matrix of metaphysical concepts. The author-rishīs tip-toe through ontological and conceptual difficulties with the help of myths and metaphors. Dr. Paul Deussen gives an extensive review[14] of the vedic literature and says…… “The motive of the conception that dominates all these passages may be described to be the recognition of the first principle of the universe as embodied in nature as a whole, but especially and most of all in the soul (the universal and the individual) Hence the idea arose that the primeval being created the universe, and then as the first born of the creation entered into it.”

The various Hymns of Creation in vedic writings dwell on this Brahman – Ātman dichotomy in a variety of ways – it is like a matrix of metaphysical concepts. The author-rishīs tip-toe through ontological and conceptual difficulties with the help of myths and metaphors. Dr. Paul Deussen gives an extensive review[14] of the vedic literature and says…… “The motive of the conception that dominates all these passages may be described to be the recognition of the first principle of the universe as embodied in nature as a whole, but especially and most of all in the soul (the universal and the individual) Hence the idea arose that the primeval being created the universe, and then as the first born of the creation entered into it.”

(See Appendix –‘Poetry’ – “MAN” by A.C. Swinburne)

Let us first look at a part of Brihad-āranyaka Up. 1.4.10 – The First adhyāy belongs to the Madhukānd – and its fourth Brāhmana is titled “The Creation of the World fom the Self” by S. Radhakrishnan….

Indeed, this world was in the beginning Brahman itself, which alone knew itself. And it realized : “I am Brahman !” – Through that it became this world. And whoever among the gods became aware of this (through the knowledge : ‘I am Brahman’), he became just the same; and so also among the Rsis (seers) as also among men. Realizing this, Vāmadeva, the Rsi exclaimed[15] :-

“I was once Manu, I was once the Sun.” And also even today he, who realizes this “ I am Brahman,” becomes this universe: and also the gods have no power to produce that which he will not. Because he is the soul (Ātman) of the same. Now he, who adores any other godhead (than the Ātman, the self) and says :”It is different, and I am different”, does not know; he is just like a domestic animal of the gods…..

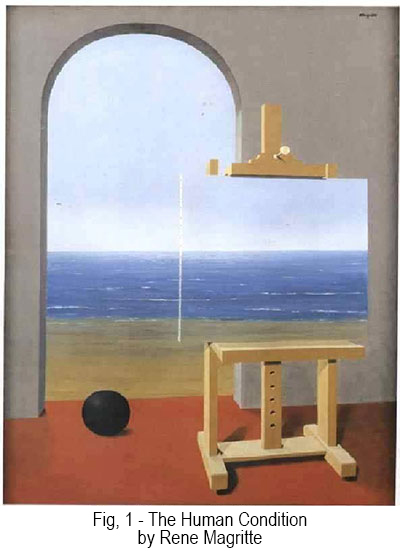

This shlöka includes the second of the Māhāvākyas . It very succinctly relates the Unknown, Brahman to the Ātman. This, the individual consciousness, realizes “Itself” as the central, “I”, …..Douglas R. Hofstadter[16] explains this beautifully when he introduces M. C. Escher’s ‘The Drawing Hands’ as, what he calls, the Tangled Hierarchy…….

Here a left hand (LH) draws a right hand (RH), while at the same time, RH draws LH. Once again , levels which ordinarily are seen hierarchical – that which draws, and that which is drawn – turn back on each other creating a Tangled Hierarchy. Note, that behind this lurks the undrawn but the drawing hand of M. C. Escher, creator of both the LH and RH.

Thus there are three hands in this lithograph – Brahman the undepicted hand of the artist ; LH and RH both simultaneously appearing as Ātman, the soul, the participator and “I”, the individual consciousness, the observer.

◊ Let us quickly look at the ‘etymology’ of aham [17] …..it is given in explicit detail in the Aitareya Āranyaka[18] in the 2nd part, 3rd adhyāy, 6th to the 8th verse. The ‘Hymn of Creation’ comes next, which is the Aitareya Upanisad itself, from the 4th to the 6th adhyāy of the Āranyaka.…

……. ‘a’ is the whole of speech and being manifested through the mutes and the sibilants it becomes manifold and various. If uttered in a whisper it is this prāna, if forcefully, that body – śarīra. Therefore it is hidden, as hidden as the previous body encapsulated in this prāna . But spoken forcefully it is that body and visible, for body is visible.

‘a’ ( A )[19] is a suffix in every sparś or ‘mute consonant’ – i.e from ( k ) to ( ma ) and in the sibilants ( Sa¸ Ya¸ sa¸ h ). This is a very interesting structure in Sanskrit. Now not only ‘a’ ( A ) is a suffix in every consonant of the alphabet and from there it pervades into every spoken word or sentence, it is also the symbol for Brahman, the Unknown……and this is precisely what is stated in 2.3.8.6….

Brahman is called ‘a’ ( A ) and the individual ‘I’ is there contained.

This is reconfirmed in Gīta 10.33…

I am the letter ‘a’ among the vowels of the alphabet and the dwanda compound in relation to the words collectively. I am endless time. I am the Dispenser facing everywhere.[20]

Lord Visnu himself proclaimed – I am the ‘a’ among the vowels.

Now ‘a’ ( A ) is the immutable, the symbolic Unknown – if, this is the ‘whisper’ –as explained in Ait. Ār. II.3.6 above, then as we force the breath just a little, what we get is its aspirate sound ‘ah’ ( Ah ). This can also be written as ( A: ) which is the visarga sound, and is grouped as ‘a-yogavāha’ meaning : “those (sounds) that occur (in the actual language) without being part of the alphabet” ….another very interesting aspect of the structure of Sanskrit language !

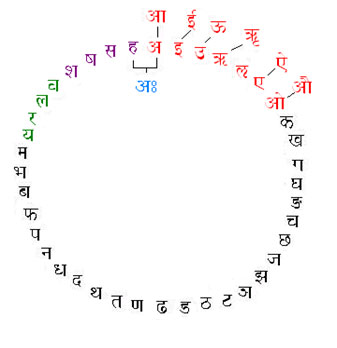

If we see the Fig.3 – another level of symmetry emerges – ‘ah’ ( A: )[22] closes the circle pictorially signifying the internal – external division . The ‘individual ego’, the ahamkār ( AhMkar ) has taken form – there is an inside and there is an outside – with the language of consciousness as the dividing membrane ! Fig. 3 – The Sanskrit-alphabet Ring

Fig. 3 – The Sanskrit-alphabet Ring

The last but not the least is the affirmation of this by twin shlökas of Brihad-āranyaka Up. V.5.3 & 4 – the 1st shlöka says that at the beginning of this You-niverse there was just water and from this germinated satyam, the truth which is likened to the Brahman (this shlöka gives the three syllables of satyam cited earlier). The 2nd shlöka says – what is true is the yonder sun ādityah. The purush who is there in the mandal and the purush who is here in the right eye, these two rest in each other. The 3rd shlöka invokes the Gāyatrī equating the head, arms and the legs to bhū, bhuvah, svah and says that the name of the purush in the mandal is ‘ah’ ( Ah: ). The 4th shlöka is identical to the previous except for the name of the purush in the right eye, it is aham (AhM ).

This is the Eastern basis of the Anthropic Principle. The Vedas are very firm on this Principle – “The world is because ‘I’ the individual consciousness am there to observe it – ‘I’ create my own māyā”. But before we go on to that let us look at the code & symmetry which I see in the Sanskrit language and I feel the basis of any new educational program should be to decipher this knowledge meticulously – based on metaphors, mathematics, science…..

This is the Eastern basis of the Anthropic Principle. The Vedas are very firm on this Principle – “The world is because ‘I’ the individual consciousness am there to observe it – ‘I’ create my own māyā”. But before we go on to that let us look at the code & symmetry which I see in the Sanskrit language and I feel the basis of any new educational program should be to decipher this knowledge meticulously – based on metaphors, mathematics, science…..

[See Appendix – ‘Poetry’ – “ I ” ( Āmi ) by R. Tagore]

◊ Erwin Scrhödinger was one of the main exponents of QM and was responsible for combining the wave and particle duality in one mathematical framework – called Complex Numbers. As we count backwards – let us say from 5 we go 4, 3, 2, 1 and we reach zero[23] , which is our famous, universally accepted contribution to the numbers game. Beyond this start the negative numbers or -1, -2, -3, and so on. Any number can be ‘squared’ that is multiplied by itself however the reverse is only true of positive numbers. That is the ‘square root’ of 4 is written as √4 and is the number 2 – because 2 X 2 = 4. The ‘square root’ of three is not a whole number but it can show up on a calculator as 1.73205…and when this is multiplied by itself we come back to 3 or 2.9999 (due to calculator decimal limit)…However there is no square root of -1, or √-1 is an undeterminable quantity and can only be represented by a symbol. And this symbol is ‘i ’. (This actually stands for the word imaginary since these numbers originated in the 16th century as ‘imaginary’ solutions for the quadratic and cubic equations of Algebra[24]). A Complex Number ‘ z ’ is written as…..

z = a + i b ……here ‘a’ is called the real part and ‘b’ the imaginary part. The beauty of this formalism is that we can do all sorts of arithmetical jugglery with ‘ z ’ as if it is just one variable but it carries with it two concepts simultaneously – that of the real ‘a’ and that of the unreal or imaginary ‘b’. And this is exactly what Scrhödinger used to integrate the duality of QM[25]. He carried the ‘particle’ concept of matter as the real part and the ‘wave’ concept as the imaginary part of the Complex Number and instead of ‘ z ’ called the variable ‘ψ ’, the Greek letter ‘psi’. (looks like the trishul doesn’t it !) [26]. This was one of the major breakthroughs of early 20th century science and the entire basis of semiconductors and subsequent electronic revolution is based on this synthesis.

Now to sum up….to my mind the Sanskrit language is this and much more the – ( A ) is like √-1, a symbol that stands for an undeterminable quantity ; ( h ) for the imaginary part and ( ma ) for the real part. Words like ayam ( Ayama\ ); ātma ( Aa%ma ); idam ( [dma\ ); adah ( Ad: ) etc… seem to be framed on the same lines, with the same type of coding.

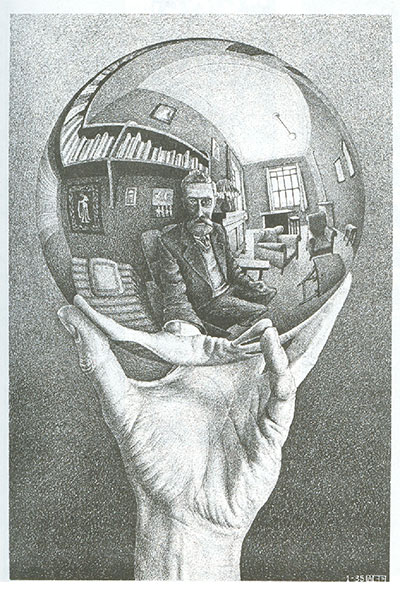

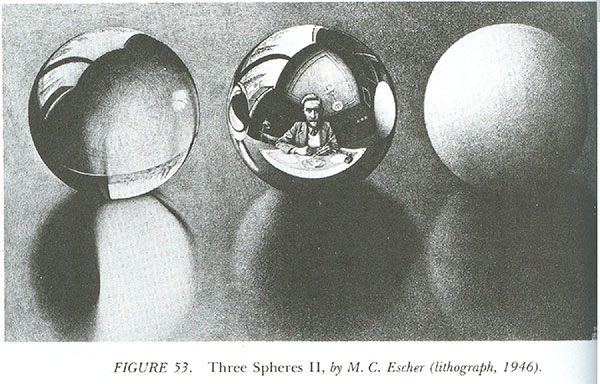

Hofstadter, in his book Gödel, Escher & Bach – “Consider ‘The Three Spheres’ in which every part of the world seems to contain, and be contained in, every other part: the writing table reflects the spheres on top ofit, the spheres reflect each other, as well as the writing table, the drawing of them, and the artist drawing it. The endless connections which all things have to each other is only hinted at here, yet the hint is enough. The allegory of “Indra’s Net” tells of an endless net where every individual ātmā is a crystal bead. The great light of “Absolute Being” illuminates and penetrates every crystal bead; moreover, every crystal bead reflects not only the light from every other crystal in the net – but also every reflection of every reflection throughout the universe…..To my mind, this brings forth the image of renormalized particles: in every electron, there are virtual photons, positrons, neutrinos, muons and so on each in every other….But then another image rises: that of people, each one reflected in the minds of many others, who in turn are mirrored in yet others, and so on.

Hofstadter, in his book Gödel, Escher & Bach – “Consider ‘The Three Spheres’ in which every part of the world seems to contain, and be contained in, every other part: the writing table reflects the spheres on top ofit, the spheres reflect each other, as well as the writing table, the drawing of them, and the artist drawing it. The endless connections which all things have to each other is only hinted at here, yet the hint is enough. The allegory of “Indra’s Net” tells of an endless net where every individual ātmā is a crystal bead. The great light of “Absolute Being” illuminates and penetrates every crystal bead; moreover, every crystal bead reflects not only the light from every other crystal in the net – but also every reflection of every reflection throughout the universe…..To my mind, this brings forth the image of renormalized particles: in every electron, there are virtual photons, positrons, neutrinos, muons and so on each in every other….But then another image rises: that of people, each one reflected in the minds of many others, who in turn are mirrored in yet others, and so on.

◊ Let us then look at the Sanskrit Alphabet itself, its varnas ( vaNa- ) , its structures, its symmetries….

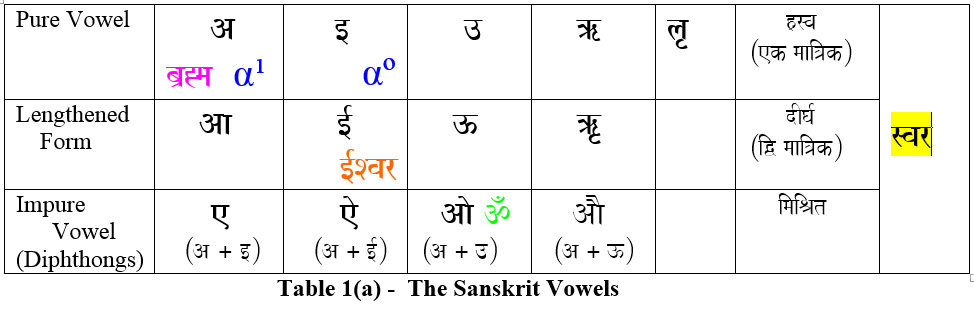

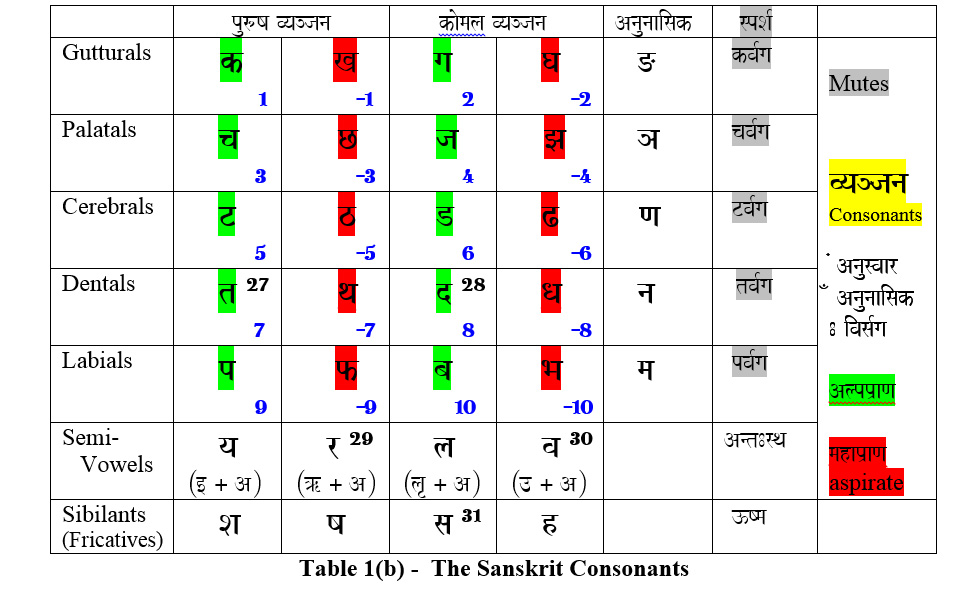

Table 1. The Sanskrit Alphabet

Notes for the Sanskrit Alphabet – for extempore explanation

Notes for the Sanskrit Alphabet – for extempore explanation

- The Sanskrit alphabet reflects the symmetries of the macrocosm around us into an arrangement of varnas that can virtually give rise to all microcosmic sounds in our lives. This universe as we are now understanding is non-linear, its vast energies entwine in yet mysterious ways, giving rise to islands of order and chaos as symmetries within endless symmetries.[32] In a linear, idealistic world energy lends itself to simple cause and effect solutions – I push this object and it moves forward – in a non-linear equation this is not so. A push here may not result in an immediate effect there, the effects may collect over ‘space and time’ zones to precipitate entelechies , sudden occurrences or epiphanies which seem totally disconnected. Or small effects can cause huge changes. The Global weather is the first non-linear equation widely studied on the super-computers since the 80’s and the ‘El-Nino factor’ is now legendary. A small current in the Pacific has been empirically found to control huge changes in world weather.

- An isomorphism from external reality to discursive language is created, thus : as we speak the first vowel ‘a’ ( A ) to the last mute ‘m’ ( ma ) – the glottis to the labials are traced and the entire mouth is virtually ‘shaped’ in the varnas. Next, the svars , or vowels are 13 in number according to the Atharvaveda Prātiśākhya and Rgveda Prātiśākhya . (Some texts talk about more, but I feel this number is correct.) – ‘a’ ( A ) is the symbol for Brahman as shown above. The vowels are likened to the energies of the day and the consonants to the night.[33] The ( A ) if suppressed, and treated as the Unknown; the Unseen or the the Undeterminable it leaves us with 12 signs. These are the number of months of the sun-signs. ‘a’ ( A ) is further embedded as a suffix in every mute and sibilant directly[34] and in the semi-vowels inherently – thus It constitutes every spoken word, sentence and so on. The mutes are the manifested, reflected glory of the Brahman and are likened to the night. They are 25 in number and so is the number of synodic moon cycles[35] in a year multiplied by two – to account for the waxing and waning part of the cycle. This is one symmetry. If we treat the mutes and sibilants( and neglect the anunāsik ) as one group then we see 12 combinations of alp & māhāprāna. Pt.Motilal Shastri explains in detail[36] how the chhands are derived from the annual, apparent movement of the sun from the tropic of Cancer to the tropic of Capricorn. The immediate solar cycles are thus embedded in the spoken word…

- The Nirukta derives svar as the sūvarna or pure sounds. The ( A: ) sound is the pratyāhār for the entire alphabet – and ( ! ) for the vowels and the mutes : that is the varnas covering the shape of the mouth. This is further corroborated by the the Chakra system[37] : ( A: ) is the bīja for the 7th and the highest Chakra or the Crown – Sahasrāra Chakra ; ( ! ) is the bīja for the next highest, the 6th or the Third-eye – Āgyā Chakra ; ( h ) for the 5th or the Throat – Viśudh Chakra.

( A ) and ( [ ) are explained as two Infinities – pūrnam adah ( Ad: ) & pūrnam idam ( [dma\ ) in the Shānti Pāth. This links beautifully with Cantors’ theory of Transinfinite cardinals – where the ‘countable infinity’ is …. αº (aleph-naught) ; the uncountable infinity of the continuous line e.g. is …. α¹ (aleph-one), and Omega that which cannot be reached.[38]

[To my mind like ( A ) is symbolically and akin to √-1 , similarly the other 3 primary vowels also have possible other mathematical symbolic representations. As a suggestion this could work on the lines that ( [ ) is the exponential ‘e’; ( ] ) is like π and ( ? ) is like the number system ?? There is a mathematical coding….but this needs to be investigated further.]

The mutes also begin with ( kM ) as Prajāpatī and ( KM ) as shūnya or zero. Both are also equated to Brahman representing the increasing side and decreasing side of creation.

- The Semi – Vowels are the antahstah or they reflect the inner energies. Their significance in the Chakra system is that they comprise the bīja for the first four Chakras viz. ( ya ) the 4th or the Heart – Anāhat Chakra ; ( r ) the 3rd or the Navel – Manipūr Chakra ; ( va ) the 2nd or the genitals – Swādhisthān Chakra ; ( la ) the 1st or the lower Pelvic – Mūldhār Chakra. It would be interesting to look at these and some conjugal words e.g. yam ( yama ) – māyā ( maayaa ) ; vis ( ivaYa ) – śiva ( iSava ) ; there is a metaphysical representation which is need further perspicacity.

- The Sibilants, also called the Fricatives are the Ūsma ( Sa ), ( Ya ), ( sa ) and ( h ) . These can be linked to the three Shaktīs ( SaR ), ( ]Yaa ), ( satI )…the energies of the manifest universe. Their consorts are Brahmā , Viśnu and Shiv…the two different ś and s….conjugate words. In the Vedic system energy is treated very differently from the western scientific method.

shri is the countable domain. Here the energy transactions are conserved. That is what leaves one spot diminishes from there and increase at the receiving end.

usā is that which keeps getting replenished from without. It is like the continuous infinity α¹…the rays of the ādityah the sun, the flowing rivers are all examples of this form of śakti.

satī is the ‘energy that grows’ by giving. It is like the fruits of a tree that multiplies or the dispersion of knowledge or like lighting many candles with one and so on. This increase is the brh and is the process of going back into the non-linearity.

There are many metaphors of these in the scriptures.

In short this alphabet of the Sanskrit language has a metaphysical basis, a structure which needs far more analysis…. its root forms, its metres and other structures give one the feeling of the unfolding of Dimensions. In fact it feels, looking at the – Fig.3 that this could well lead to elusive string of the western ‘string theory’ of 12 to 26 dimensions ?

APPENDIX – ‘Poetry’

Brahma

by Ralph Waldo Emerson

(From ‘A Concise Treasury of GREAT POEMS ’ by Louis Untermeyer – Pocket Books)

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882) – Born May 25,1803, in Boston, Massachusetts, of ministerial stock, he was destined for the ministry. After graduating from Harvard College and Harvard Divinity School, he was ordained in his 26th year. Three years later he left the pulpit, unable to believe in the ritual.

Emerson spoke up for the intellectual as well as religious independence ; he held that humanity had lost self-rule and self-reliance, that man was dominated by things rather than by thought. As a result of Emerson’s attack on the conventions, clergymen assailed his “heresies” and Harvard closed its lecture rooms to him. Thirty years later he received an honorary degree from Harvard and chosen one of its overseers. At sixty-seven he gave a course of philosophy at Cambridge.

The suavity of Emerson’s verse is deceptive. The surface is so limpid, so easily persuasive, that it appears conventional. But the ideas embodied in the poems are energetic and radical ideas ; they are, like Emerson himself, not only truth-loving but truth-living. They celebrate the democratic man, but they do not idealize him ; they recognize evil as well as good ; they regard doubt not as fixed denial but as “a cry for faith rising from the dust of dead creeds.” Even love, which demands every sacrifice, must be free from moral impositions; for “when half-gods go, the gods arrived.”

The pantheistic BRAHMA has been parodied and misunderstood, although the title should make it plain that the speaker is not meant to be Emerson but the god of nature. In this poem, accident and design, life and death, are harmonized in the all-resolving paradox of existence.

If the red slayer think he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain,

They know not the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again.

Far or forgot to me is near;

Shadow and sunlight are the same;

The vanished gods to me appear;

And one to me are shame and fame.

They reckon ill who leave me out;

When me they fly, I am the wings;

I am the doubter and the doubt,

And I the hymn the Brahmin sings.

The strong gods pine for my abode,

And pine in vain the sacred Seven;

But thou, meek lover of the good !

Find me, and turn thy back on heaven.

MAN

by A. C. Swinburne

(From ‘A Concise Treasury of GREAT POEMS ’ by Louis Untermeyer – Pocket Books)

Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837 – 1909) has been variously described than any other poet of his century. Edmund Gosse pictured him, with his thin body, waving red hair, and birdlike head, as a brilliant but ridiculous flamingo. T. Earle Welby likened him to a pagan apparition at a Victorian tea party.

The personality who, according to Edgell Rickword, “shattered the virginal reticence of Victoria’s serenest years with a book of poems,” was born in London April 5, 1837. His forebears were distinguished aristocrats. Spoiled and precocious, Swinburne attended Eton and Oxford without being graduated from either. He fell in love with medievalism and its interpretation by the Pre-Raphelites. In his early twenties he attempted to outdo the excesses of the young Bohemians, and was successful, although at great cost to his physique and character.

At twenty-three Swinburne published his first volume, two poetic dramas dedicated to Rossetti. The blank verse was fluent, and the interspersed lyrics were graceful, but the critics were not impressed. Five years later there appeared his ATLANTA IN CALYDON, and the critics squandered there superlatives. In this Swinburne attempted to “reproduce for English readers the likeness of a Greek tragedy with something of its true poetic life and charm.” But the exuberance was anything but Greek, and the mounting syllables carried a sumptuous and orchestral music new to English ears. The spirit was rebellious, a defiance of the creeds by which men live, but it was the melodiousness which made the young men of the period shout the choruses to each other. ‘MAN’ the poem below was part of ATLANTA IN CALYDON :-

Before the beginning of years,

There came to the making of man

Time, with a gift of tears ;

Grief, with a glass that ran ;

Pleasure, with pain for leaven [39] ;

Summer, with flowers that fell ;

Remembrance fallen from heaven ;

And madness rises from hell ;

Strength without hands to smite ;

Love that endures for a breath ;

Night, the shadow of light,

And life, the shadow of death.

And the high Gods took in hand

Fire, and the falling of tears,

And a measure of sliding sand

From under the feet of the years ;

And froth and drift of the sea ;

And dust of the laboring earth ;

And bodies of things to be

In the houses of death and of birth ;

And wrought with weeping and laughter,

And fashioned with loathing and love,

With life before and after

And death beneath and above,

For a day and night and a morrow,

That his strength might endure for a span

With travail and heavy sorrow,

The holy spirit of man.

From the winds of the north and the south

They gathered as unto strife ;

They breathed upon his mouth,

They filled his body with life ;

Eyesight and speech they wrought

For the veils of the soul therein[40],

A time for labor and thought,

A time to serve and to sin ;

They gave him light in his ways,

And love, and a space for delight,

And beauty and length of days,

And night, and sleep in the night.

His speech is a burning fire ;

With his lips he travaileth ;

In his heart is a blind desire,

In his eyes foreknowledge of death ;

He weaves, and is clothed with derision ;

Sows, and he shall not reap ;

His life is a watch or a vision

Between a sleep and a sleep[41].

from ATLANTA IN CALYDON

“ I “ (Ämî)

by Shri Rabindranath Tagore

(Extract from ‘The Concept of an Indian Literature’)

Man happens to be the fulcrum of Tagore’s cosmic vision ; it is the “ the Religion of Man” that concerns him ; there is , indeed, no other religion. Because man is, there is Dharma ; because man is, there is Beauty and Truth – and, indeed God. There is a taped conversation between Einstein and Tagore, in 1934, where Tagore keeps insisting that Beauty and Truth are dependent on man, and argues that if man did not exist the Pallus Athene would no longer be beautiful. Einstein counters that Beauty may be dependent on man but he cannot believe that Truth is. Truth, according to him, exists independent of man ; if all human beings disappeared from the face of the earth, Truth would remain. “I agree with this conception in regard to Beauty,” says Einstein, “ but not in regard to Truth.”

A famous poem in Shyamali, “ I ”, is built on this Tagorean interpretation of the Upanishadic mantra – “Tat-tvam-asi” – “That you are”[42]. The point is that if I indeed am That, if the individual Atman is the cosmic Brahmān, then the two are not , as traditional Upanishadic glosses assert, identical but, argues Tagore, interdependent. God needs man as man needs God. In fact, in the poem that follows, a startling twist is given to the concept of maya. In Tagore’s view, there are two kinds of maya – the no-maya that “exists” when there is no creation, no mankind, a pre-creation existencs, as it were. And there is a yes-maya, the world of shape and colour and music and thing, of the multiplicity of material phenomena. No-maya is helpless and lost and alone and nothing, unless it expresses itself in the yes-maya of the physical world. Brahmān, alone, without the presence of man, is not the essence, the Truth, the basic reality; you might say, empty, insubstantial, vacuous. If God creates man, it is equally true that man creates God, because God’s existence is proved and approved by God’s creation of mankind.

This may be a meeting point of science and myth ; who can say ? Tagore’s is not a smoky abstraction. At least one gets the impression when reading the views of John A. Wheeler, Professor at Princeton University and currently Director of the Centre for Theoretical Physics at the University of Texas, who in a seminal book Gravitational Theory and Gravitational Collapse gave it the name “black hole” – to a miniscule object hugely dense and “yet invisible because nothing, not even light, could escape its stupendous gravity”.

“Is man an unimportant bit of dust or an important galaxy somewhere in the vastness of space ?” asks Wheeler. And his answer is no – not on the basis of religious faith but on scientific argument. “The strongest feature of Quantum Mechanics, the foundation of modern physics, is the discovery that it is impossible to measure more than one quantity (such as position or momentum) of sub-atomic particles at a time ; measuring the one prevents us from measuring the other…..This ‘uncertainty principle’ stood for forty years as a paradox and an apparent limit to human knowledge.” The words are John Boslough’s, who also explains how Wheeler takes up this strange uncertainty principle and concludes that “what we can say about the universe as a whole depends on the means we use to discover it. If to measure a particle is to decide which of its properties has a tangible reality, then a physicist is not simply an observer – but an active participant ! Man by exploring the universe, plays a part in bringing into being something of what he sees. This was a modification of the ‘anthropic principle’ first advanced by physicist Robert Dicke. The universe is the way it is because we are in it. Wheeler pushed the idea to its limits, to a principle cutting both ways ; that the concept of a universe is meaningless unless there is a community of thinkers to observe it, and that community is impossible unless the universe is adapted form the start to giving rise to life and mind.

Tagore would have agreed : objective reality does not exist without subjective perception of it. Not a leaf falls without some creative grief and compassionate sacrifice involved.

The emerald became green because I willed it so

and the ruby red.

Because I raised my eyes to the sky

the sky blazed up

in the east and the west.

I looked at the rose and said “Beautiful”–

and the rose was beautiful.

“But that’s philosophy,” you say,

“Why don’t you stick to poetry ?”

To which I’ll say, “But this is the truth.

That’s why its poetry.”

Of course I’m proud :

I’m speaking for man.

The World-Maker’s skill

is woven on the fabric of man’s I-ness.

The philosopher chants with every breath–

“No, no, no,

no emerald, no ruby, no light, no rose,

no I, no you.”

But there is the Infinite One deep in sadhana

in the heart of finite man,

saying, “you and I are one.”

In that oneness of you and I darkness and light become one,

rose shape, rose rasa,

no-maya flowered into yes-maya,

in line and colour, in pain and pleasure.

Don’t call this philosophy,

My heart thrills with the joy of creation

as I stand brush and colour-bowl in hand

in the hall of this cosmic-I.

The pundits say :

Look at the old man Moon

smiling his cruel and cunning smile

crawling like a messenger of Death

to the ribs of Earth.

One day he’ll tug at our seas and hills.

A new account will open on the ledger of history

with a huge zero entered by Mahakala Time

erasing past debits like days and nights.

What then of pretentious immortal deeds of man ?

Tidbits of history swallowed

in the black ink of oblivion.

The day man disappears

his eyes will take away all the world’s colours.

The day man disappears

his heart will take away all the world’s rasa.

Then Shakti vibrations alone will energise the sky,

there will no light anywhere.

The musician’s fingers will strum in a veena-less hall

a soundless raga.

A poem-less Creator will sit alone

in a blue bereft sky

lost in the coordinates of a personality-less existence.

Then

in that cosmic mansion

stretching across endless and uncountable reaches

of space upon space of splendid desolation

these syllables will be heard no more–

“You are beautiful,”

“I love you.”

Will the Creator then lapse into sadhana again

for yuga upon yuga ?

On the evening of cosmic dissolution will he chant

“Speak to me ! Speak to me !”

Will he say, “Say ‘You are beautiful’?”

Will he say, “Say ‘I love you’?”